Nguyệt Mai đã nhận được:

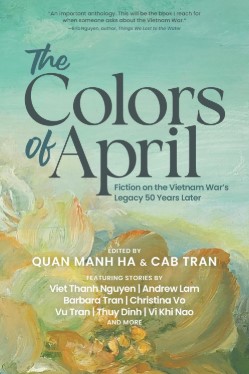

THE COLORS OF APRIL

Fiction on the Vietnam War’s Legacy 50 Years Later

Fifty years after the end of the Vietnam War, literary voices of the Vietnamese-American diaspora as well as Vietnam-based authors speak to the experience of those who left and those who stayed in The Colors Of April, a collection of new short fiction curated by award-winning translators and editors Quan Manh Ha and Cab Tran.

Edited by Quan Manh Ha & Cab Tran

Contributors: Bảo Thương, Thuy Dinh, Đỗ Thị Diệu Ngọc, Anvi Hoàng, Hoàng Phượng Mai, Lại Văn Long, Andrew Lam, Lê Phương Anh, Lê Vũ Trường Giang, Lưu Vĩ Lân, Vi Khi Nao, Ngô Thế Vinh, Annhien Nguyen, Nguyễn Minh Chuyên, Nguyễn Huy Cường, Nguyễn Thị Kim Hòa, Nguyễn Mỹ Nữ, Phùng Nguyễn, Nguyễn Thu Trân, Nguyễn Đức Tùng, Viet Thanh Nguyen, Kevin D. Pham, Tuan Phan, Gin To, Barbara Tran, Elizabeth Tran, Trần Thị Tú Ngọc, Vu Tran, Văn Xương, Christina Vo, Vũ Cao Phan, and Vương Tâm.

Publisher: Three Rooms Press (March 25, 2025)

Language: English

Paperback: 306 pages

Link to buy this book: https://www.amazon.com

***********

A Small Dream for the Year 2000

A Small Dream for the Year 2000 was written 30 years ago (January 1995), and is now included in the anthology The Colors of April: Fiction on The Vietnam War’s Legacy 50 Years Later. This title has been released on March 25, 2025 on Amazon and bookstores.

The man, a farmer, was formerly an ARVN soldier. Twenty years had passed since his days in the military, and he was now a middle-aged person. Though not yet fifty, he had been made pallid, old and decrepit by a life of unrewarding hard labor. He had lost his left foot, ironically after his military service had terminated, when stepping on a mine right in his own rice field. One did not have to be a doctor to know that his body hosted various illnesses and diseases: malnutrition, chronic malaria, and anemia. Whatever energy and dignity he retained was revealed in his bright though rather sad eyes, eyes that always looked directly at those of the person he talked to. Today, he came to this field dispensary for another kind of complaint. It concerned a bluish-black lesion on his back which was not painful, but had been oozing an ichorous discharge for a long while. He had sought various treatments, but found no hope of a cure. First, he had been made to wait in a district’s health service station where a communist doctor had eventually given him a few Western medicinal tablets; then a doctor of traditional medicine had treated him in turn with an herbal concoction and acupuncture. Despite all that, the disease refused to go away, even as he was steadily emaciating. Hearing that a group of healthcare workers from overseas had come to offer volunteer services, he decided to come to them at this dispensary and try his luck. With good fortune, he hoped, he might even be able to again meet the doctor he used to know – the chief surgeon of his Airborne Ranger Battalion in the past, who presently lived and worked in America. But it turned out that all the faces he saw were young and unfamiliar. Nonetheless, he showed them his back for examination. From the team of young doctors came an audible gasp of surprise. The heart of Toan, the team leader, seemed to miss a beat. Without the necessity of engaging in complicated diagnostic procedures, he immediately recognized a form of malignant melanoma, which certainly would have had metastases spread to other parts of the body. The disease, of course, could have been cured if discovered earlier. Unfortunately, this present case, being at an advanced stage, could not be treated even with the most elaborate and sophisticated medical technologies available in the US. It was not the patient, but the young doctor who expressed sadness: “You’ve come too late; this disease otherwise could have been treated successfully.” Betraying no embarrassment, the soldier-turned-farmer patient looked directly at the young doctor, his eyes darkened with anger and sternness: “I’ve come too late, you say? It’s you doctors who have come late, whereas myself, like all my compatriots, have been here forever.” Flatly refusing to wait for anything else from the group of unknown doctors, the man turned his back on them and walked out, limping along on his bamboo crutches, his eyes looking straight ahead, accepting his miserable lot with the same courage he had shown as a soldier in a time past.

During the preliminary meeting held in Palo Alto to set up the agenda of the Convention, it was decided that the upcoming Fifth International Convention of Vietnamese Physicians would be changed to one of Physicians, Dentists and Pharmacists. After all, intermarriage among Vietnamese practitioners of the three branches of medicine had been a very popular practice. To Chinh, that was good news reflecting the strength of unity amongst overseas Vietnamese medical professionals.

The last discussion in Palo Alto did not conclude until past midnight. Even so, the next morning, as was the habit of a person advanced in years, Chinh woke up very early and got ready for his one-day trip to Las Vegas for a visit with his son. Toan, his eldest son, in a few months would complete his four-year residency in general surgery. The younger man’s plan was to subsequently go to New York where he would spend four more years studying plastic surgery. This was a medical specialization which Toan once had remarked that a number of his father’s friends and colleagues had abused and degenerated into “prostitution of plastic surgery”, transforming it into something like a pure cosmetic industry which helped its clientele acquire more beautiful features like a high-bridged nose and fuller buttocks. Toan was strong and healthy, taller and bigger than his father. He lived very much like a young man born in the United States, quite active and aggressive in both work and play, his thoughts and actions uncomplicated. Not only Toan and his peers’ way of thinking, but also their manner of identifying legitimate issues of concern, differed greatly from the perspective of Chinh’s generation. To be born in Vietnam but live abroad, and to be a first- or second-class citizen, had never constituted a problem or issue to Toan.

Even though father and son had only one day together to talk, Toan insisted on driving Chinh to a ski resort very far from the entertainment district of Las Vegas. Along the way, Toan confided in his father that it was not accidental that he had chosen to study plastic surgery with a central focus on hand reconstruction. It was not the artistic inclination expressed in his being a notable classical guitar player that made him treasure this part of the anatomy. Rather, to him, the function of the hands was a highly valuable symbol of a life of labor and arts. Unlike his father and his peer friends, Toan was endowed with golden hands, as was the observation of his mentor professor. Indeed, from routine to challenging cases of surgery, through each and every economical slit and cut he made, Toan always came out with results that were judged state of the art. For a long time, Toan had been inspired by the example of the English orthopedist Paul Brand who worked in India. Not only with talent, but also with faith and enduring dedication, Brand had contributed enormously to the field of orthopedic surgery specializing in hand reconstruction, essentially to help people with Hansen’s disease, or leprosy. His work brought hope to millions of people afflicted by that malady, and what he had accomplished for the past four decades intrigued Toan a great deal. Recently, Toan was also deeply moved when reading for the first time a book written in Vietnamese and published abroad by a Catholic priest, a book which describes the wretched situation of leprosy camps in Vietnam, especially those found in the north. Thereupon, Toan vigorously reached the decision that it would not be Brand or any other foreign doctors, but Toan himself and his friends, who would be members of Mission Restore Hope bound for Vietnam. He mused upon the dream that the year 2000 would be when Hansen’s disease no longer posed a public health issue in his native land.

Toan related to his father that, lately, he had received in succession of letters and telephone calls from Colorado, Boston, and Houston inviting him to work in Asia, Vietnam being top priority, under very favorable conditions: a starting salary of six-digits or over a hundred-thousand dollars a year, coupled with guaranteed fringe benefits including tax-free privileges when working overseas. Toan had a resolute response to the offer: if the sole purpose was to make money, he did not need to go and work in Vietnam. He was told by those contacts that groups of Vietnamese-American doctors, not merely the vocally loud group led by Le Hoang Bao Long, but also others comprising “more brainy” physicians, had quietly gone back to Vietnam to prepare a network of market-oriented medical services. It was said that, in their vision, the first base of operations would be Thong Nhat Hospital in Saigon, which would be renovated and upgraded to American standards, and doctors serving there would all have been trained in the United States. However, what would remain unchanged was the hospital’s adherence to its priority of treating high-ranking Communist Party officials. The only difference and “renovation” it would succumb to, so as to be in line with the market economy, was to admit foreign clientele from around the world, who were rich and in possession of expensive medical insurance coverage. They would be from South Korea, Taiwan, Hongkong, America, France, Australia, Canada, and other countries. The main point was to guarantee and safeguard their health to the highest extent possible, so they would have the peace of mind to work and invest, as well as to enjoy their lives, in all corners of Vietnam, from Nam Quan Pass in the north to Ca Mau Point in the deep south. And, undoubtedly, all this would also promise fat profits, which were greedily eyed not only by American insurance companies, but also by a certain group of Vietnamese-American physicians who were eager to “go back and help Vietnam”.

At the age of thirty, Toan had his own way of thinking, clear and free, and showed self-confidence in the path of commitment he had chosen. Chinh did not exactly agree with his son’s view, but at the same time he knew only too well Toan’s firm and independent nature. Certainly Chinh did not entertain the thought of clashing with Toan for the second time over the same issue of whether or not they should go back to Vietnam and engage in humanitarian services. On the brighter side, Chinh felt relatively calmed when considering that whatever choice Toan made was prompted by pure and noble motives, which set him apart from the opportunistic crowd. And in a certain fashion, Chinh felt a little envious of Toan for his youth, and even for his gullibility, which was almost transparently obvious. At this thought, which sounded rather absurd, he shook his head and smiled to himself as he drove back to Palo Alto.

From Montreal, Canada, Chinh had more than once visited California. Despite his familiarity with the area, every visit seemed to have given him the impression of seeing anew Vietnamese communities with expanding renovations and animated activities. Instead of the slightly-over-an-hour flight, Chinh had decided to rent a car from Hertz at the airport and drive from Palo Alto to Little Saigon in the heart of Orange County. The trip was toward a young city of the future, but simultaneously it was for him also a journey backward into the past, a trip taken in part to contemplate a time lost. To confront future problems faced by Vietnam at the threshold of the 21st century, even against the cold, hard background of political reality, one needed not only to utilize one’s brain, but also to pair it with one’s heartfelt emotions, he thought. The evil demon was seen not exclusively in the communist specter; it was lodged in our own hearts, hearts that remained callous.

One of the statements made by Thien, Chinh’s friend and colleague, meant as a joke, kept haunting him. Tongue in cheek, Thien had said that if a mad fanatic were to shoot and kill Le Hoang Bao Long, labeled pro-communist, how desolate Little Saigon would certainly become. Then perhaps a second Le Hoang Bao Long would need to be found to take his place in provoking anti-communist sentiment among the Vietnamese community, for without anti-communist fervor as a stimulant, Little Saigon would not be able to retain its liveliness. The only thing was, it was not easy to pin down the communists, their target ever shifting and treacherous; and given that tricky situation, unwittingly, communist hunters were also made to move in pursuit, only to voluntarily come full circle in no time at all, and naturally from the first round of shots verifiable losses were counted among their very friends.

Chinh planned to meet with Thien, author of Project 2000. The aim of the project, which Chinh thought bold and appealing, was to coordinate all circles of overseas physicians with a view to “exploiting and transforming the abundant talent and energy existent in the world into resources available to Viet Nam; opening the hearts of people to tap a sector of the world’s prosperity and channel it to the land of their birth; shaping the destiny of Vietnam by modern technologies prevalent all over the world”. The plan was to establish a non-profit co-op group wherein each doctor, each dentist, and each pharmacist would contribute US $2,000.00, merely a very small tax-deductible amount set against very big income taxes paid every year in their adopted countries. With participation of the thousand members, the acquired budget would come to a sum of two-million dollars in cash. Given that financial potential, there would be nothing that the International Association of Vietnamese Physicians, Dentists and Pharmacists could not do: from responding immediately to urgent matters like aiding fellow-countrymen caught as victims in violent disturbances in Los Angeles or helping victims of floods in the Mekong delta; to long-term projects like building a Convention Center together with a Vietnam Culture House and Vietnamese Park adjacent to Little Saigon; participating decidedly, and in timely fashion, in a health project designed by WHO, the World Health Organization, for eradication of leprosy in Vietnam by the year 2000. Chinh was aware that right in the heart of Little Saigon alone, among the silent majority, there existed many kind-hearted and sincere souls.

There was the colonel, former commander of an Airborne Ranger Group, who had just arrived in the U.S. after fourteen years in a communist prison. Paying no mind to the care of his own failing health, the colonel had immediately sat down and composed a letter to Chinh requesting that Chinh, on the strength of his good reputation, help motivate Vietnamese immigrants to re-create the sculpture called Thuong Tiec, ‘Mourning’, so that soldiers who had lost their lives for the freedom of South Vietnam would not be forgotten. The original large statue was a well-known work by Nguyen Thanh Thu, featuring a soldier sitting on a rock, his rifle in his lap, his dejected expression suggesting a deep sorrow widely interpreted as representing his mourning for his fallen fellow fighters. It had been placed in front of the National Military Cemetery midway between Saigon and Bien Hoa. Hours after the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, the Communists had pulled down the sculpture and destroyed it.

Then there was Tien, Chinh’s former collegiate fellow, who had taken the oath as a member of the Boy Scouts of Vietnam at an assembly on Mount Bach Ma, near the city of Hue. He held but two passions: to restore the organization of the Boy Scouts of Vietnam abroad for the benefit of youths, and to establish the first Vietnamese hospital in America.

Of special note was Nguyen, Chinh’s former senior colleague. Almost 60, he still remained single. For so many years, Nguyen had continued without fail to be a devoted friend to Indochinese boat people, and also a physician, gracefully free of charge, serving circles of writers and artists, as well as HO families (those who immigrated to the U.S. under the Orderly Departure Program). Lien, another doctor who had come to the local scene rather late from a refugee camp on an island, was determined to fight, against all odds, to undergo intensive retraining so as to be able to practice medicine again in his new homeland. Even so preoccupied, Lien did not give up on his ardent dream of bringing into existence a monumental sculpture of “Mother Holding Her Child” plunging into the immense ocean and drifting to another horizon, which art work would symbolize the huge exodus of two million Vietnamese who were on their way to creating a super Vietnam in the heart of the world. Chinh could think of numerous other symbolic characters and noble thoughts, yet at the same time he asked himself why, in spite of all that, he and his friends continued to lose touch with one another in the darkness of “arrogance, envy and delusion”, to use Thien’s words.

For a few decades now, Chinh had remained a tormented soul, an intellectual witnessing. tragedies in a time of turmoil and of glittering and bright deception. In the midst of so much noise and the reverberation of depraved words and expressions, surrounded by false political realities, very often Chinh wanted to retreat into tranquility and quietude, doing away with tortuous thoughts which only caused personal distress and did not seem to do anyone any good. But he would not be himself if he chose to walk that path. Forever, he would definitely be himself, a man of strong conviction. To use electronic computer terminology, he had been programmed, and, as such, there could be no question of change or alteration in his pattern. The only possibility he could imagine was that he might try to become more sensitive – to the extent that he would feel amenable to dialogue with viewpoints different from his own, all of which he believed could come together in the end, even though the result would be a rainbow coalition. But, after all, multiple forms and colors are the ferment of creativity, he thought. Chinh realized that the number of people who were still with him and supported him was dwindling with time. Not opposing him openly, the others simply detached themselves from his sphere and each chose to walk his own way. As for Chinh, certainly for the rest of his life, he would continue on the straight path he had drawn for himself, no matter how deserted it grew. The ready forgetfulness and compromise exhibited by overseas Vietnamese – which Chinh considered damaging to their political dignity and refugee rights – together with the extreme joy shown by people inside Vietnam because of the so-called doi moirenovation, only served to sharpen his heartache.

In the end, everyone tries to accommodate himself to new circumstances in order to survive, Chinh told himself. A life abounding in instinct is ever ready to shed old skin, to change colors, and to proceed with fervor. The very few people who were as highly principled and constant as himself seemed to be facing the possibility of becoming an endangered species. Chinh’s mother, hair completely white with age, still lived in Vietnam. One of his dreams was simple: that real peace would come to his homeland, so he could go back to see his mother before she passed away, and to visit his old village and watch children play in the village school yard. What a great happiness it would be if he were able once again to provide medical care to familiar peasants who were ever honest and simple, from whom the fees he had received sometimes were no more than a bunch of bananas, some other varieties of fruit, or a few newly laid chicken eggs. His dream was seemingly not so unattainable, yet it still appeared beyond reach and far into the future. The reason was, he firmly told himself, because he could not, and would not, return to his country as a mere onlooker, as a tourist, or even worse, as a comprador shamelessly flaunting his financial success. Though he longed to see his mother, Chinh could not by any means return to Vietnam in his present state of mind and current external circumstances.

Since the middle of the 1970’s, following the fall of South Vietnam, there had been a massive influx of Indochinese refugees spreading all over the United States, the greatest concentration of them being in California. Difficulties faced by those who had arrived first were not few. To their camps, like Pendleton and Fort Chaffee, humane and generous American sponsors had come to give them aid and moral support. On the darker side, there was also no shortage of local residents who discriminated against them, who held ill feelings toward them and wanted to send them back to where they had come from. “We Don’t Want Them. May They Catch Pneumonia and Die”, so went a slogan. Among that first mass of refugees were Chinh’s former colleagues. Currently, the number of Vietnamese doctors had reached 2000 in the United States alone, not counting smaller numbers living in Canada, France, Australia, and a few other countries. Out of a total of about 3000 physicians in the whole of South Vietnam, more than 2500 had exited the country. This was not unlike a general strike staged by the entire medical profession, a strike which had prolonged itself from 1975 until the present. Chinh knew for sure that he himself had been one of the few who had effectively mobilized and led that endless and unprecedented strike.

Chinh had a clear itinerary in mind. He would visit various places: San Jose in Silicon Valley, valley of high-tech industries; Los Angeles, the city of angels that ironically was about to become a twin sister of Ho Chi Minh city; Orange County, the capital of anti-communist refugees, in which is located Little Saigon; and San Diego, known to have the best weather in the world. All these locations were full of Vietnamese, and their population kept increasing, not only because of the newly arrived, but also due to the phenomenon of a “secondary migration” of Vietnamese from other states. In the end, thus, after having settled elsewhere, they chose to move to California, a place of warm sunshine, of familiar tropical weather just like that in the resort city of Dalat in Vietnam, as they told one another.

Eventually, the Vietnamese immigrants embraced standardization, a very American particularity. Big and small, cities in America all look alike, with gas stations, supermarkets, fast food restaurants like McDonalds. Likewise, entering crowded and bustling Vietnamese shopping centers on Bolsa avenue, one readily sees, without having to spend any time searching, restaurants specializing in beef noodle soup “pho”; big and small supermarkets; pharmacies; doctors’ offices; lawyers’ offices; and, naturally, newspaper offices, given the insatiable Vietnamese appetite for news in print.

Chinh’s colleagues had been among the first group that arrived in this land. They represented a collective of academic intellectuals most of whom, with help from a refugee services program extended to all refugees like themselves, had quickly returned to practicing their profession in extremely favorable conditions. After that, if only everyone of them had retained good memories about their initial feelings and emotions when forced to abandon everything and to risk their lives departing for an unknown destination, they would have conducted their lives differently in exile, Chinh began silently grumbling to himself. Engraved in Chinh’s memory were those days in an island refugee camp where Ngan, one of Chinh’s former colleagues, once and again had confided that he only wished to set foot in the United States some day, having no dream of venturing to any further place, that he held no high hope of practicing medicine again, that happiness and contentment for him would be no more than breathing the air of freedom, living like a human being, starting all over from the beginning to set up a home solely by manual labor, and sacrificing himself for the future of his children. Luckily, reality had turned out better than what Ngan had expected. With his intelligence and relentless energy, and, of course, with luck as well, only within a short period had he become one of those who resumed their medical practice. To work as physicians in America meant to belong to the upper middle class, and, therefore, the status and position accruing to this group of newly certified doctors was a dream even for many native-born American citizens.

But Ngan and a number of others in the profession had not felt content to stop there. And, eventually, what was inevitably to happen had happened. Concerted police raids on a number of Vietnamese doctors’ offices uncovered what was labeled as “the biggest medical fraud in the history of the State of California”. The news made headlines in newspapers and television networks all over the United States. By then, only nine years had passed since the fall of South Vietnam, a traumatic occurrence which was still an unmitigated nightmare for its displaced people. And these same displaced people had to face the humiliating February 1984 medical scandal, a second nightmare of an entirely different nature. The name Vietnam had never been mentioned so very often as it was in the entire week that followed. Nor had the past ever been so cruelly violated. This event was indeed an ignominy to the past of South Vietnam and its people, a past defined by many sacrifices for a righteous cause. The image of a horde of Vietnamese doctors and pharmacists, Ngan among them, handcuffed by uniformed police, seen in the streets, exposed to sun and wind, had been thoroughly exploited by American newspapers and television networks. All members of Vietnamese communities felt their honor damaged by this scandal, which instilled in them a feeling of insecurity and fear. In fact, immediately afterwards, there had arisen a wave of abuse which local people flung at Vietnamese refugees in general. In factories and companies, some insolent employees in a direct manner rudely referred to their Vietnamese co-workers as thieves, while others in a more indirect fashion stuck American newspaper clippings, complete with photos of the event, on the walls around the area where many Vietnamese worked. Those average honest Vietnamese citizens, who had come to the United States empty-handed, who were trying to re-make their lives out of nothing except their will and industrious hands, suddenly became victims of a glaring injustice projected by discrimination and contempt. Choked with anger, a Vietnamese worker screamed to the absent academic intellectuals, that even way back in the old country, any time and any where these intellectuals had been happy and lucky, so it was about time they showed their faces in his workplace to receive this disgraceful humiliation they themselves had brought about.

The scandalous event of almost a decade ago appeared as though it had occurred just the day before, so heavy was the flashback that flooded Chinh’s mind. He tried to liberate himself from stagnant residues of memory about a woeful time in the past. He pressed a button and automatically the car windows were rolled down, admitting from the ocean a strong breeze which flapped noisily against the interior of the car. Blue sky and blue ocean – it was exactly the same deep blue spreading over the two opposite shores of the Pacific Ocean. The sight brought to mind a Chinese statement Chinh had learned while in prison without knowing its origin: “The sea of suffering is so immense that when you turn your head you cannot see the shores.” Freeway 101 along the Pacific coast triggered his memory of National Highway One in the beloved country he had left behind on the other side of the ocean. Over there was seen the same great sea formed from the tears of living beings, the same stretches of glistening sand, the same fields of white salt, the same rows of green coconut trees. The homeland in memory would have been absolutely beautiful, if not for the intrusion of flashback-like film strips projecting scenes “along Highway One”, showing the “highway of terror” and “bloody stretches of sand” during the last days of March, 1975.

Little Saigon, his destination, is always considered the capital of Vietnamese refugees, Chinh reflected. In a certain sense, it is indeed an extension of the city of Saigon in Vietnam. On the other hand, if one cares to look at historical records of this geographical area and its people, one will note an irony of history, which is that the first Vietnamese to live in Orange County was an ugly Vietnamese named Pham Xuan An, a communist party member. On the surface, he was known to work for ten years as a correspondent for the American TIME magazine. What nobody knew then was that he was at the same time a high ranking spy for Hanoi. Supported by a fellowship from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of South Vietnam, An went to the United States to study in the late 1950s. After graduation, he traveled all over America, and ended up settling in Orange County. Subsequently, An returned to Saigon where he worked for the British Reuters news agency, then for TIME until the last day of South Vietnam. Only much later did one learn that An had joined the Viet Minh, ‘Vietnamese Independence Brotherhood League’, very early on, in the 1940s. Initially, he had worked as a not-so-important messenger and guide, and finally had become a strategic spy who, under the cloak of a correspondent for the prestigious American magazine, had escaped detection by various CIA networks. Now, in the 1990s, An lived quietly in Saigon, witnessing first-hand the failed revolution which he had loyally and wholeheartedly served for more than forty years. In the meantime, it was estimated that about three hundred thousand Vietnamese lived in Orange County, where An had previously established his residence. If An had a chance to come back, he would not be able to recognize the area at all. From a dead place with poorly developed orange orchards, it had become a youthful and bustling Little Saigon. In spite of all the hardships they shared with their parents as the first generation of Vietnamese immigrants, many children proved very successful in school and at college, and helped raise the standards of local education a step higher. They graduated in every field of study. This was more than what could have been hoped for from Dong Du – the Go East Movement – in the first decade of the twentieth century, which sent Vietnamese students to Tokyo for modern education. After a period of less than two decades in the United States, the Vietnamese produced for the future of Vietnam a whole stock of experts who could serve all areas of Vietnam’s social and economic life.

In his life of exile, not being able as yet to directly contribute anything to his homeland, Chinh nonetheless nurtured a small dream for the year 2000. After attending many conventions, he had the impression that he and his friends and colleagues were still like homeless people, even though they were lodged in no less than four-star hotels. In view of that, he decided that during this present field trip to California, the first item of construction he would campaign for was not merely a home base for the International Association of Vietnamese Physicians, but more extensively, a Cultural Park complex comprising a Convention Center, a Museum, a Culture House, and a Park. It ought to be a representative project of great scale and high quality, which would be given utmost attention in various stages of construction. As much as the village’s dinh lang, or communal house, symbolizes the good of the village, the proposed Culture Park complex would be an embodiment of cultural roots, indispensable roots that should be jealously safeguarded by generations of Vietnamese immigrants from the first days they set foot in this new continent of opportunities. The complex would be like a common ground for the currently very divisive Vietnamese diaspora, and would help younger generations advance with pride in their adopted country, while looking toward Vietnam for their true identity. It was envisioned that the Cultural Park complex would be built in the southwestern part of the United States, specifically located in a large area south of highways 22 and 405, adjacent to Little Saigon. It would be a place conducive to a lively introduction to unique Vietnamese cultural traits, through attempts to re-enact periods of history, both glorious and tragic, of the Vietnamese people since the establishment of their country. This project would not solely be the job undertaken by a Special Mission Committee composed of the cream of the diaspora, drawn from all areas of social activities, Chinh thought. Rather, it had to be a work of the whole community of free overseas Vietnamese, without discrimination on the basis of differences displayed by individuals and various camps. To begin with, if each immigrant simply contributed a dollar per year, Chinh estimated, there would be more than a million dollars in addition to the two million expected from the Association of Physicians, Dentists and Pharmacists, and whatever else from the Society of Professionals and business people. Three million dollars per year was by no means a small amount with which to build the foundation for Project 2000. The first five years would be spent in identifying and acquiring a piece of land big enough to meet the requirements for the Cultural Park complex. Of the buildings, the convention center would be the first to be erected, for it would serve as a cradle of community activities in culture and the arts. Thinking these thoughts, Chinh at the same time could not forget how many times he had heard the so-tiresome refrain of dismissal that Vietnamese were incapable of constructing works of great scale, because so many destructive wars, in addition to the humid weather of tropical Asian monsoon, would not allow any great man-made work to survive. But like himself, they were in the United States now, and he wanted to prove the fallacy of their argument. After all, the essential element was still man. As long as he had a dream worthy to be called a dream. Then what was needed was a cement substance to bandage and join broken pieces in the larger heart. More than once, Chinh had proved his ability to lead an intellectual community that had consistently did nothing for the last two decades. Now he was confronted with a reverse challenge, that of mobilizing the strength of the same collective to do something, if not inside Vietnam then outside, within an end-of-the-century five-year plan, before the 21st century arrived. He dreamed of a five-year period significant with planning and action, not with a passive attitude of simply watching things run their course.

But reality told another story, Chinh reminded himself. After but a few tentative first steps of sounding out others’ feelings, Chinh had come to clearly realize that it was indeed easy for members of the Association of Physicians to agree on non-cooperation with the Vietnam government in everything, including humanitarian aid. On the other hand, it was a much more complicated problem when it came to a concrete plan which demanded participation and contribution from everyone, resulting in numerous questions of “why and because” issued from the very people whom Chinh thought to be his close friends, having walked a long way with him. Given this state of affairs, Chinh thought, the upcoming Fifth Convention would be a challenging testing ground for the willingness, not only of himself but also of the whole overseas Vietnamese corps of medical professionals, to commit themselves to this meaningful cultural project.

From Chinh’s point of view, instead of standing as onlookers from the outside, the International Association of Vietnamese Physicians should play a pioneering role, getting directly involved from the beginning in the construction of the Cultural Park complex. The building of it would be a rehearsal, serving as the blueprint of a model for the museum of the Vietnam War envisioned by ISAW, Institute for the Study of American Wars, an American NGO. ISAW was planning to build Valor Park in Maryland comprising a series of museums dedicated to seven wars in which the Americans had been directly involved since the foundation of their country. Of course, among the seven was the Vietnam War, the only war of just cause lost by the United States, along with its South Vietnamese allies. Providing correct facts and searching for answers to the question of causes would have to be the proper contents of this future Vietnam War Museum. Surely, two million people who had left their native country in a huge exodus could not accept a second defeat, an eternal one at that, at Valor Park, imposed upon them by a repetition of falsified historical facts, manipulated by the communists as usual. In fact, if things went according to ISAW’s plan, the museum would exhibit incomplete, one-sided testimonies which would show, for example, that the war was between the United States and North Vietnam, ignoring the role of South Vietnam in the conflict. It was not simply a matter of who had won and who had lost. Rather, it involved the political personality of two million refugee immigrants who were struggling for a free political system in the land of their birth.

Furthermore, Chinh believed that the process of constructing the Vietnam War Museum by ISAW had to start by drawing from the planned project of the Vietnamese Cultural Park complex of 2000, to be located right in the capital of Vietnamese refugees. This Park was to represent an overview and a selection of images, data, and testimonies related to various historical periods of the Vietnamese struggle for independence. It was intended to be a place where younger generations of Vietnamese immigrants could get help to look toward Vietnam in search of a lost time, to fully understand why they were present in this new continent. In such light did the envisioned Cultural Park complex constitute Chinh’s dream.

Between Chinh and his son Toan there transpired a silent conflict with regard to the battlegrounds of their dreams. Toan’s dream was thousands of miles away, back in the native homeland. But then, Chinh asked himself, what dream can’t one dream, inside the country or out? Realization of any dream did not depend solely on the brave heart of one person; it had to be based on the will of a collective whole that together looked in one direction, together cherished and longed for the joy of a fulfilled dream. As for Chinh personally, what he was wishing for was not a temple to worship in, but a warm sweet home for “A Hundred Children, A Hundred Clans” – Vietnamese descending from the mythological union of the fairy Au Co and the Dragon King Lac Long Quan. This home base would be a location where values of the past were collected and stored, a gathering place where the ebullient spirit of life in the present was demonstrated, and a starting point from which to challenge the course of the future. It was to be, above all, a pilgrimage destination for every Vietnamese no matter where in the world he or she lived.

Ngô Thế Vinh

Little Saigon, California 01/1995 – 04/2025

Little Saigon, California 01/1995 – 04/2025

*********

Giấc Mộng Con Năm 2000 _ Ngô Thế Vinh

Giấc Mộng Con Năm 2000 được viết cách đây 30 năm (01.1995), nay được chọn đưa vào tuyển tập The Colors of April với nhiều người viết, như “Di Sản của Chiến Tranh Việt Nam 50 Năm Sau.” Sách sẽ được chính thức phát hành vào ngày 25 tháng 3 năm 2025 trên Amazon và các nhà sách.

CÂU CHUYỆN CUỐI NĂM. Người đàn ông nông dân ấy gốc lính cũ, hai mươi năm sau đã bước vào tuổi trung niên, chưa tới tuổi năm mươi nhưng cuộc sống lao động lam lũ khiến anh ta trông xanh xao và già xọm. Anh mất một bàn chân trái khi đã mãn lính do đạp phải mìn ngay trên ruộng nhà. Không cần là bác sĩ cũng biết là anh ta mang trên người đủ thứ bệnh tật: thiếu ăn suy dinh dưỡng, sốt rét kinh niên và thiếu máu. Tất cả sinh lực và nhân cách của anh là nơi đôi mắt sáng tuy hơi buồn nhưng luôn luôn nhìn thẳng vào mặt người đối diện. Hôm nay anh tới đây vì một lý do khác. Một mảng đen bầm nơi lưng không đau rỉ nước vàng từ bấy lâu, trị cách gì cũng không hết. Chầu trực lên trạm y tế huyện được y sĩ cách mạng cho ít viên thuốc tây, rồi đến thầy đông y cho bốc thuốc nam và cả châm cứu nữa mà bệnh thì vẫn không chuyển trong khi người anh cứ gầy rốc ra. Nay nghe có đoàn y tế thiện nguyện ở ngoại quốc về, anh cũng muốn tới thử coi, biết đâu anh lại được gặp ông thầy cũ - người y sĩ trưởng của anh năm nào. Và rồi anh chỉ gặp toàn những khuôn mặt trẻ lạ, nhưng anh vẫn cứ đưa lưng ra cho người ta khám. Một tiếng ồ rất đỗi kinh ngạc của cả toán. Tim người bác sĩ trẻ trưởng đoàn như lạc một nhịp. Không cần một chẩn đoán phứctạp Toản nhận ra ngay đây là một dạng ung thư mêlanin ác tính - malignant melanoma, chắc chắn với di căn đã tràn lan. Dĩ nhiên căn bệnh có thể trị khỏi nếu phát hiện sớm; nhưng trường hợp này cho dù với phương tiện tiên tiến nhất trên đất Mỹ cũng đành bó tay. Chẳng phải là người bệnh mà là người thầy thuốc trẻ nói giọng buồn bã: Ông tới trễ quá, lẽ ra bệnh có thể trị khỏi... Bệnh nhân không tỏ vẻ bối rối, anh vẫn nhìn thẳng vào mặt người thầy thuốc, ánh mắt tím thẫm xuống vừa giận dữ vừa nghiêm khắc: Tới trễ? Chỉ có bác sĩ các ông là Những Người Tới Trễ chứ tôi cũng như mọi người dân vẫn ở đây từ bao giờ... Dứt khoát không chờ đợi một điều gì thêm ở đám thầy thuốc xa lạ ấy, anh quay lưng bước ra khập khễnh trên đôi nạng tre mắt vẫn nhìn thẳng về phía trước, khắc khổ cam chịu và vẫn can trường như một người lính thuở nào.

Hội nghị Y sĩ Thế giới lần thứ 5 sẽ là một Đại hội Y Nha Dược. Với Chính đó là một tin vui biểu hiện sức mạnh đoàn kết của ngành y ở hải ngoại. Buổi họp cuối cùng ở Palo Alto kết thúc quá nửa khuya, sáng hôm sau như thói quen của người có tuổi, Chính vẫn dậy rất sớm chuẩn bị cho một ngày đi Las Vegas thăm con. Chỉ còn mấy tháng nữa Toản -- đứa con trai lớn của Chính, hoàn tất bốn năm Thường trú Giải phẫu tổng quát. Sau đó nó sẽ đi New York học tiếp thêm 4 năm về giải phẫu bổ hình. Một ngành mà đã có lần Toản cho là một số các bác bạn của ba đã tha hóa -- prostitution of plastic surgery, biến thành kỹ nghệ sửa sắc đẹp nâng mũi đệm mông. Toản khỏe mạnh, cao lớn hơn bố, sống như một thanh niên sinh đẻ ở Mỹ, rất năng động xông xáo trong công việc cũng như giải trí vui chơi; suy nghĩ và hành động đơn giản. Không phải chỉ cách suy nghĩ mà cách đặt vấn đề của tụi nó cũng khác xa với thế hệ của Chính. Sinh đẻ ở Việt nam sống ở nước ngoài, là công dân hạng nhất hay hạng hai, chưa bao giờ là một “issue” đối với nó.

Tuy chỉ có một ngày để cho hai bố con gặp nhau hàn huyên, nhưng Toản vẫn lái xe đưa bố lên một khu trượt tuyết rất xa khu giải trí Las Vegas. Toản tâm sự với bố là không phải tình cờ mà nó chọn đi về chuyên khoa bổ hình mà chủ yếu là phẫu thuật bàn tay. Chẳng phải chỉ vì Toản có tâm hồn nghệ sĩ, là tay chơi guitare classic có hạng mà nó biết quý bàn tay của nó. Với Toản chức năng đôi bàn tay là một biểu tượng vô cùng quý giá của cuộc sống lao động và nghệ thuật. Khác với bố và các bạn đồng lứa, Toản may mắn được trời cho đôi bàn tay vàng. Ông giáo sư dạy Toản đã phải thốt ra như vậy. Trong mọi trường hợp từ thông thường tới những “cas” mổ đầy thử thách, qua từng nét rạch đường cắt rất tiết kiệm, trường hợp nào cũng được đánh giá như là đạt tới mức nghệ thuật -- “state of art”. Từ lâu Toản đã bị thuyết phục bởi tên của một bác sĩ chỉnh hình Anh Paul Brand, phục vụ tại Ấn độ, người mà không phải chỉ với tài năng mà còn cả với niềm tin và sự tận tụy can đảm đã có nhiều cống hiến to lớn trong lãnh vực phẫu thuật phục hồi bàn tay cho người bệnh Hansen, đem lại hy vọng cho hàng triệu người bệnh trên khắp thế giới. Toản đã thích thú theo dõi các công trình của Brand trong suốt bốn thập niên qua. Gần đây Toản cũng đã vô cùng xúc động khi lần đầu tiên được đọc một cuốn sách tiếng Việt xuất bản ở hải ngoại của một linh mục nói về thực trạng bi thảm của những những trại cùi ở quê nhà nhất là ở miền Bắc. Toản tâm niệm sẽ không phải Brand hay một bác sĩ ngoại quốc nào khác mà là chính Toản và các bạn sẽ là thành viên của Chiến dịch Phục hồi Hy vọng -- Mission Restore Hope. Toản mơ một giấc mơ năm 2000, bệnh Hansen không còn là vấn đề y tế công cộng nơi quê nhà.

Toản tâm sự với bố là gần đây đã liên tiếp nhận được những thư và các cú điện thoại mời mọc từ Colorado, Boston, Houston để về làm việc tại Á châu, ưu tiên là ở Việt Nam với những điều kiện hết sức là hấp dẫn: lương khởi đầu 6 digits nghĩa là trên trăm ngàn đô la một năm, đi kèm theo bao nhiêu những bảo đảm quyền lợi khác kể cả không phải đóng thuế khi làm việc ở hải ngoại. Toản có thái độ dứt khoát: nếu chỉ vì mục đích làm giàu, con chẳng cần phải trở về Việt nam. Họ cũng cho con biết đã có những phái đoàn Bác sĩ Mỹ gốc Việt, không phải chỉ có nhóm lớn tiếng ồn ào như Lê Hoàng Bảo Long mà còn những toán khác “có đầu óc hơn” âm thầm lặng lẽ đi về chuẩn bị cho mạng lưới y tế thị trường này. Cơ sở đầu tiên sẽ là bệnh viện Thống Nhất, sẽ được tân trang và upgrade đúng tiêu chuẩn Mỹ và bác sĩ hoàn toàn được đào tạo tại Mỹ. Không có gì thay đổi là bệnh viện ấy vẫn ưu tiên điều trị cho các cán bộ cao cấp. Chỉ có khác và “đổi mới” cho phù hợp với kinh tế thị trường, đây còn là nơi chữa trị cho khách ngoại quốc có bảo hiểm giàu tiền bạc thuộc bốn biển năm châu. Nam Triều tiên có, Tàu Đài Loan có Tàu Hồng kông có, Mỹ Pháp, Uc Gia nã đại, có đủ cả. Làm sao bảo đảm sức khỏe cho họ với tiêu chuẩn cao nhất để họ yên tâm khai thác làm ăn và cả hưởng thụ trên khắp ngõ ngách của Việt Nam từ ải Nam quan cho đến mũi Cà Mau. Và đây cũng là món lợi nhuận béo bở không phải chỉ có các hãng bảo hiểm Mỹ đang muốn nhảy vào mà phải kể tới đám bác sĩ Mỹ gốc Việt cũng đang nao nức rất muốn “về giúp Việt nam.” Chưa qua tuổi 30, Toản suy nghĩ trong sáng độc lập và tự tin trên bước đường dấn thân của nó. Không hẳn là Chính đã đồng ý, nhưng lại rất hiểu tính cứng cỏi độc lập của con, Chính không muốn có lần đụng độ thứ hai giữa hai bố con. Chính tạm yên tâm khi thấy con mình cho dù với chọn lựa nào cũng thôi thúc bởi những động lực trong sáng, nó không thể lẫn vào đám bọn người cơ hội. Và theo một nghĩa nào đó, Chính thấy hơi ganh tỵ với tuổi trẻ và sự cả tin đến trong suốt của con; rồi cho đó như một ý nghĩ kỳ quái anh lắc đầu tự mỉm cười khi một mình lái xe đổ dốc trên con đường về...

Hơn một lần viếng thăm Cali, nhưng mỗi chuyến đi đều đem lại cho Chính những cảm tưởng đổi mới của những cộng đồng Việt nam rất sinh động. Thay vì chỉ hơn một giờ bay, Chính đã quyết định thuê một chiếc xe của hãng Hertz từ phi trường, đích thân lái từ Palo Alto về tới Little Saigon. Chuyến đi hướng về một thành phố trẻ trung của tương lai nhưng cũng lại là một cuộc hành trình ngược về quá khứ nhìn lại khoảng thời gian đã mất. Anh nghĩ cho dù trong bối cảnh lạnh lùng của thực tế chính trị, đương đầu với những vấn đề của Việt Nam tương lai ở ngưỡng cửa thế kỷ 21, không phải chỉ có vận dụng bộ óc mà phải là sự hoà hợp với rung động của con tim. Quỷ dữ không chỉ là bóng ma cộng sản mà ngay chính cõi lòng sao vẫn cứ chai đá của chúng ta.

Tuy chỉ là câu nói đùa của Thiện nhưng sao vẫn cứ ám ảnh Chính mãi. Rằng nếu có tên quá khích điên khùng bắn chết Lê Hoàng Bảo Long, chắc Little Saigon sẽ buồn bã biết chừng nào. Chắc rồi cũng phải tìm cho ra một Lê Hoàng Bảo Long thứ hai. Không có chống cộng thì còn đâu là sự sinh động của Little Saigon. Chỉ có điều cộng sản thì ẩn hiện, lúc nào mục tiêu cũng di động và xảo quyệt, vô hình chung bọn chúng đã khiến các tay xạ thủ chống cộng cũng di chuyển để rồi tự nguyện sắp theo đội hình vòng tròn tự lúc nào và dĩ nhiên ngay từ loạt súng đầu tiên tổn thất có thể kiểm kê được là nơi chính các đồng bạn... Chính có dự định sẽ gặp Thiện -- tác giả của Project 2000, nhằm kết hợp toàn y giới ở hải ngoại mà Chính cho là táo bạo và hấp dẫn với quan niệm “vận dụng và chuyển hoá tài lực của thế giới thành tài lực của Việt Nam, khai thông những hưng thịnh của thế giới chuyển đổ về quê hương, thực hiện vận mạng Việt Nam bằng những phương tiện của thế giới”... Dự trù hình thành một tổ hợp vô vị lợi, mỗi Y Nha Dược sĩ đóng 2000 mỹ kim như một phần khấu trừ thuế rất nhỏ trong phần thuế khóa rất lớn mà họ đóng góp hàng năm trên các vùng đất tạm dung đang cưu mang họ, thì với một ngàn người tham gia số tiền hành sự đã lên đến 2 triệu đô la tiền mặt, với tiềm năng ấy thì không có việc gì mà Hội y nha dược Thế giới không làm được, từ đáp ứng tức thời như cứu trợ đồng bào nạn nhân trong bạo loạn ở Los Angeles, nạn nhân bão lụt thiên tai ở đồng bằng sông Cửu Long, đến các công trình dài hạn như xây dựng Convention Center - Nhà Văn hoá Công viên Việt Nam cạnh thủ đô Little Sài gòn, tham gia dứt điểm một dự án y tế của OMS thanh toán bệnh Hansen ở Việt Nam vào năm 2000... Chính thấy rằng chỉ ngay trong trái tim Tiểu Sài Gòn ấy giữa đa số thầm lặng đã có biết bao nhiêu người có lòng có cái tâm thành: ông Đại Tá chỉ huy đơn vị cũ với thành tích 14 năm tù mới sang được tới Mỹ trong tình trạng sức khỏe suy kiệt chẳng biết lo thân đã ngồi viết ngay thư đầu tiên liên lạc với Chính yêu cầu anh với uy tín sẵn có giúp ông vận động dựng lại được bức tượng Thương Tiếc để mọi người không quên những người lính đã chết. Tiến người bạn đồng môn, gốc tráng sinh Bạch Mã chỉ có hai niềm say mê: phục hồi phong trào Hướng Đạo Việt Nam tại hải ngoại cho giới trẻ và thiết lập một bệnh viện Việt Nam đầu tiên trên đất Mỹ. Nguyễn lớp đàn anh của Chính, tuổi ngót 60 rồi mà vẫn còn độc thân, vẫn bền bỉ trong bấy nhiêu năm liền là người bạn thiết tận tụy của thuyền nhân và cũng là thầy thuốc miễn phí của giới văn nghệ sĩ các gia đình H.O. Liên một bác sĩ muộn màng mới từ đảo qua đang sống mái ngày đêm đèn sách để trở lại hành nghề nhưng vẫn tích cực mơ ước thực hiện một tượng đài vĩ đại Mẹ Bồng Con lao vào đại dương theo nước non ngàn dặm ra đi -- biểu tượng cho một cuộc di dân khổng lồ của 2 triệu người Việt đi khai sinh một siêu Việt Nam trong lòng thế giới... và còn biết bao nhiêu, bao nhiêu những điển hình và ý nghĩ tốt đẹp khác nữa, vậy mà -- Chính tự hỏi, tại sao anh và các bạn vẫn lạc nhau trong bóng đêm của “kiêu khí, đố kỵ và mê chướng,” lại vẫn theo ngôn từ của Thiện.

Bao nhiêu chục năm rồi, Chính vẫn là con người trăn trở, vẫn là trí thức chứng nhân của những bi kịch của một thời nhiễu nhương và lừa dối hào nhoáng. Giữa rất nhiều ồn ào và tiếng động của ngôn từ sa đọa và những thực tế chính trị giả dối, nhiều lúc Chính cũng muốn tĩnh lặng, từ bỏ những suy nghĩ khúc mắc, chỉ làm khổ chính anh và cảm tưởng như cũng chẳng ích gì cho ai; nhưng như vậy thì anh đâu còn là Chính nữa. Trước sau anh vẫn là anh, con người của xác tín. Dùng ngôn từ của điện toán, thì con người anh đã được thảo chương -- programmed, chẳng thể nào mà nói đến chuyện đổi thay, chỉ có thể anh sẽ nhạy cảm hơn, chấp nhận đối thoại với những khác biệt mà anh tin rằng vẫn có thể có đoàn kết, cho dù đó là một liên kết nhiều màu sắc -- rainbow coalition, và theo anh sự đa dạng chính là chất men của sáng tạo. Anh hiểu rằng số người còn theo và ủng hộ anh ngày càng ít đi. Không ra mặt chống anh nhưng họ tách ra và mỗi người chọn đi theo hướng riêng của họ. Riêng anh chắc hẳn rằng trong suốt phần cuộc đời còn lại, anh sẽ vẫn cứ đi trên con đường thẳng băng đã vạch ra cho dù quạnh quẽ. Sự mau quên và thỏa hiệp của những người Việt hải ngoại -- mà anh cho là thương tổn tới nhân cách chính trị và quyền tỵ nạn của họ, cộng thêm với sự vui mừng quá độ của người dân trong nước trước những điều được gọi là “đổi mới” chỉ làm cho anh thêm đau lòng. Rồi ra ai thì cũng tìm cách thích nghi để mà tồn tại, cuộc sống ngồn ngộn bản năng thì vẫn cứ dễ dàng thay da đổi màu và bừng bừng đi tới. Số rất ít người cứng rắn nguyên tắc và nhất quán như anh hình như đang có nguy cơ trở thành một chủng loại hiếm hoi sắp bị tiêu diệt - endangered species. Chính còn lại bà mẹ già bên Việt Nam, mái tóc đã trắng bạc như sương. Anh mơ một giấc mơ đơn giản, cũng chỉ mong đất nước thanh bình để kịp về thăm mẹ, về thăm ngôi làng cũ, ngắm đàn trẻ thơ nô đùa nơi sân trường làng, và hạnh phúc biết bao nhiêu khi được trở lại khám bệnh chăm sóc cho những nông dân thân thuộc bao giờ cũng đôn hậu và chất phác mà y phí có khi chỉ là một nải chuối ít trái cây hay mấy hột gà tươi. Ước mơ có gì là cao xa đâu nhưng sao vẫn ở ngoài tầm tay và có vẻ như còn rất xa vời. Bởi vì anh vẫn dứt khoát tự nhủ lòng mình anh sẽ không thể và không bao giờ trở lại quê hương như một kẻ bàng quan, một khách du lịch hay tệ hơn nữa như một tên mại bản với vênh vang áo gấm về làng. Mặc dầu rất muốn gặp mẹ nhưng anh vẫn không thể nào về với tâm cảnh và ngoại cảnh bây giờ.

Kể từ giữa thập niên 70, cùng với sự sụp đổ của miền Nam, là một làn sóng ồ ạt dân tỵ nạn Đông Dương rải ra khắp nước Mỹ, nhưng đông đảo nhất vẫn là tiểu bang Cali. Khó khăn của những người tới sớm không phải là ít. Từ ngoài các căn cứ Pendleton, Fort Chaffee không phải chỉ có những bảo trợ người Mỹ giàu lòng bác ái tới giúp đỡ họ mà cả không thiếu những người điạ phương kỳ thị thù ghét trù ẻo và muốn đuổi họ về nước. “We Don’t Want them, May They Catch Pneumonia and Die…”. Và Trong đám người tỵ nạn ấy đã có các đồng nghiệp của Chính. Cho tới nay con số bác sĩ Việt Nam lên tới 2000 chỉ riêng ở Mỹ, chưa kể một số không ít khác sống ở Canada, Pháp và Uc châu và một số nước khác. Hơn 2500 bác sĩ trên tổng số 3000 của toàn miền Nam đã thoát ra khỏi xứ, không khác một cuộc tổng đình công của toàn ngành y tế, liên tục kéo dài từ 75 tới nay. Chính cũng biết rất rõ anh là một trong số ít người đã vận động và lãnh đạo một cách có hiệu quả cuộc đình công dài bất tận một cách không tiền khoáng hậu ấy.

Chính sẽ lần lượt ghé thăm: San Jose thung lũng điện tử hoa vàng, Los Angeles thành phố thiên thần nhưng lại sắp kết nghĩa với thành phố mang tên Hồ chí Minh, Orange thủ đô tỵ nạn chống cộng với Sài Gòn Nhỏ và San Diego nơi nổi tiếng khí hậu tốt nhất thế giới – đều là những nơi có đông đảo người Việt, và con số ấy tiếp tục gia tăng không phải chỉ bởi những người mới tới; mà còn do hiện tượng “di dân lần thứ hai” của những người Việt đã tới sinh sống ở những tiểu bang khác, cuối cùng rồi cũng lựa chọn trở về Cali nơi có nắng ấm, có khí hậu nhiệt đới giống Việt Nam như ở Đà Lạt, họ nói với nhau như thế.

Tiêu chuẩn hoá, đó là đặc tính rất Mỹ. Thành phố lớn nhỏ nào ở Mỹ thì cũng rất giống nhau, với những trạm xăng, các siêu thị và những tiệm fast food Mac Donald. Đi vào những phố chợ Việt nam sầm uất ngay trên đường Bolsa là thấy những tiệm phở, các siêu thị lớn nhỏ, phòng mạch bác sĩ, hiệu thuốc tây, các văn phòng luật sư và dĩ nhiên cả những tòa báo.

Các đồng nghiệp của Chính đã có mặt ngay từ đầu trong số đông đảo những người tới sớm. Họ biểu tượng cho một tập thể trí thức khoa bảng, được sự giúp đỡ của chương trình tỵ nạn như mọi người, đa số đã mau chóng trở lại hành nghề trong những điều kiện hết sức thuận lợi. Sau đó phải chi ai cũng có trí nhớ tốt về những cảm xúc đầu tiên khi dứt bỏ hết mọi thứ bất kể sống chết ra đi. Chính còn nhớ như in về những ngày ở trên đảo, Ngạn đã nhiều lần tâm sự là chỉ mong có ngày đặt chân tới Mỹ anh chẳng bao giờ còn mơ ước tới một nơi nào xa hơn nữa, cũng chẳng hề có cao vọng trở lại nghề cũ mà hạnh phúc nếu có là được hít thở không khí tự do, được sống như một con người và được khởi sự lại từ đầu, gây dựng mái gia đình bằng sức lao động của tay chân, hy sinh cho tương lai thế hệ những đứa con. Nhưng sự thể lại tốt hơn với mong đợi, chính Ngạn bằng trí thông minh nghị lực làm việc và dĩ nhiên cả may mắn nữa, chỉ trong một thời gian ngắn anh là một trong số những người trở lại hành nghề rất sớm. Là bác sĩ ở Mỹ có nghĩa là đã thuộc vào thành phần xã hội trung lưu trên cao, địa vị hoàn cảnh của họ là ước mơ ngay cả đối với rất nhiều người dân Mỹ bản xứ. Nhưng Ngạn và một số người khác đã không dừng lại ở đó. Và điều gì phải đến đã đến. Hậu quả là một cuộc ruồng bố được mệnh danh là “gian lận y tế lớn nhất trong lịch sử tiểu bang Cali”. Để trở thành tin tức hàng đầu nơi trang nhất của báo chí và các đài truyền hình khắp nước Mỹ. Mới chín năm từ ngày sụp đổ cả miền Nam đang còn là một cơn ác mộng chưa nguôi, biến cố tháng Hai 1984 là một cơn mộng dữ thứ hai nhưng với bản chất hoàn toàn khác. Chưa bao giờ hai chữ Việt Nam lại được nhắc tới nhiều như thế trong suốt tuần lễ. Cũng chưa bao giờ quá khứ bị đối xử tàn nhẫn đến như thế. Cảnh tượng hàng loạt bác sĩ dược sĩ trong đó có Ngạn bị các cảnh sát sắc phục còng tay ngoài đường, bêu trước nắng gió đã bị báo chí Tivi Mỹ khai thác triệt để. Ai cũng cảm thấy bị thiệt hại về mặt thanh danh, cộng thêm với những cảm giác bất an và sợ hãi. Rõ ràng sau đó đã có một làn sóng nguyền rủa của người dân bản xứ nhắm chung vào người Việt tỵ nạn. Trong các xưởng hãng bọn sỗ sàng trực tiếp thì xách mé gọi các đồng nghiệp Việt Nam là đồ ăn cắp, hoặc gián tiếp hơn họ cắt những bản tin với hình ảnh đăng trên báo Mỹ đem dán lên tường chỗ có đông các công nhân Việt Nam làm việc. Những người dân Việt bình thường lương thiện, tới Mỹ với hai bàn tay trắng, đang tạo dựng lại cuộc sống từ bước đầu số không, bằng tất cả ý chí và lao động cần mẫn của đôi bàn tay nay bỗng dưng trở thành nạn nhân oan khiên của kỳ thị và cả khinh bỉ. Có người uất ức quá đã phải la lên: hỡi các ông trí thức khoa bảng ơi, ngay từ trong nước bao giờ và ở đâu thì các ông cũng là người sung sướng, sao các ông không có mặt ở đây để nhận lãnh sự nhục nhã này... Chuyện xảy ra đã hơn mười năm rồi mà vẫn tưởng như mới hôm qua, như một flashback nặng nề diễn ra trong đầu óc Chính. Hiện giờ anh cố chủ động thoát ra khỏi những ngưng đọng của ký ức về một giai đoạn bi ai quá khứ. Đưa tay bấm nút tự động hạ mở kính xe, gió biển thổi cuộn vào trong lòng xe vỗ phần phật. Trời xanh biển xanh, vẫn màu xanh thiên thanh ấy, có gì khác nhau đâu giữa hai bờ đại dương này. Khổ hải vượng dương, hồi đầu thị ngạn. Ở đâu thì nỗi khổ cũng mênh mông, nhìn lại chẳng thấy đâu là bờ. Con đường 101 dọc theo bờ biển Thái Bình Dương lúc này lại gợi nhớ Quốc lộ 1 bên kia đại dương trên đất nước thân yêu của chàng. Vẫn những giọt nước ấy là nước mắt và làm nên biển cả, những dải cát sáng long lanh như thủy tinh, những ruộng muối trắng, những hàng dừa xanh. Quê hương của trí nhớ đó sẽ đẹp đẽ biết bao nhiêu nếu không có những khúc phim hồi tưởng của “dọc đường số 1”, của “đại lộ kinh hoàng”, của “những dải cát thấm máu” ở những ngày cuối tháng Ba 1975.

Little Saigon vẫn được coi là thủ đô của những người Việt tỵ nạn. Theo nghĩa nào đó là một Sài Gòn nối dài. Nếu khảo sát về địa dư chí, thì như một điều trớ trêu của lịch sử, tên người Việt Nam đầu tiên đến ở quận Cam rất sớm này lại là một người Việt xấu xí -- có tên là Phạm Xuân Ẩn, một đảng viên cộng sản. Bề ngoài anh ta là một ký giả của tuần báo Times trong suốt 10 năm, nhưng điều mà không ai được biết là từ lâu anh vốn là một điệp viên cao cấp của Hà Nội. Ẩn đã từng được học bổng của Bộ Ngoại Giao đi du học tại Mỹ vào cuối những năm 50, học xong Ẩn đi tham quan khắp nước Mỹ rồi trở về sống ở quận Cam; sau đó trở lại Sài Gòn làm cho hãng thông tấn Reuters của Anh, rồi tuần báo Times của Mỹ cho tới những ngày cuối của miền Nam. Mãi sau này người ta mới được biết Ẩn đã gia nhập phong trào Việt Minh rất sớm từ những năm 40, khởi từ vai trò một giao liên chẳng có gì là quan trọng để rồi cuối cùng trở thành một điệp viên chiến lược qua mắt được bao nhiêu mạng lưới CIA với danh hiệu phóng viên rất an toàn của một tờ báo Mỹ uy tín... Hiện giờ đã có tới khoảng ba trăm ngàn người Việt đang chiếm chỗ của Ẩn trước kia. Còn riêng Ẩn thì lại đang sống lặng lẽ ở Sài Gòn, tiếp tục là chứng nhân cho cuộc cách mạng thất bại mà Ẩn đã trung thành và toàn tâm phục vụ trong suốt hơn 40 năm. Trở về với thực tại của quận Cam hôm nay, nếu Ẩn có dịp trở lại đây chắc cũng chẳng thể nào nhận ra chốn cũ. Biến từ một khu phố chết với những vườn cam xác xơ, nay trở thành một Sài Gòn Nhỏ trẻ trung và sầm uất. Con em của những người Việt mới tới, ngay từ thế hệ di dân thứ nhất đã rất thành công trong học vấn và nâng tiêu chuẩn giáo dục địa phương cao thêm một bước mới. Chúng tốt nghiệp từ đủ khắp các ngành. Hơn cả giấc mộng Đông Du, chỉ trong khoảng thời gian chưa đầy hai thập niên, nước Việt Nam tương lai có cả một đội ngũ chuyên viên tài ba để có thể trải ra cùng khắp.

Trong kiếp sống lưu dân, chưa làm được gì trực tiếp cho quê hương nhưng, Chính vẫn có thể mơ một Giấc Mộng Con Năm 2000. Trải qua bao nhiêu hội nghị, Chính có cảm tưởng anh và các bạn vẫn như những người không nhà cho dù các nơi tạm trú đều là những đệ nhất khách sạn không dưới bốn sao. Chuyến đi thực tế này, dự định rằng là bước khởi đầu vận động hình thành không phải chỉ là một mái nhà cho hội Y sĩ, mà bao quát hơn là một convention center, một toà Nhà Văn hoá, một viện Bảo tàng một Công viên Việt Nam. Đó phải là công trình biểu tượng có tầm vóc, sẽ được thực hiện ưu tiên qua từng giai đoạn. Nếu nghĩ rằng ngôi Đình là biểu tượng cho cái thiện của làng, thì khu Công viên Văn hoá ấy là biểu tượng cho cái gốc tốt đẹp không thể thiếu của các thế hệ di dân Việt Nam từ những ngày đầu đặt chân tới lục địa mới của cơ hội này, nó sẽ như một mẫu số chung rộng rãi cho một cộng đồng hải ngoại đang rất phân hóa, giúp đám trẻ hãnh tiến hướng Việt tìm lại được cái căn cước đích thực của tụi nó. Dự phỏng rằng Công viên Văn hóa sẽ được thiết lập trong vùng Tây Nam Hoa Kỳ, tọa lạc trên một diện tích rộng lớn phía bờ Nam của xa lộ 22 và 405 tiếp ráp với khu Little Saigon. Đó là nơi có khả năng giới thiệu một cách sinh động những nét đặc thù của văn hóa Việt qua những bước tái thể hiện các giai đoạn lịch sử hào hùng và cả bi thảm của dân tộc Việt từ buổi sơ khai lập quốc. Đây không phải thuần chỉ là công trình của một Uỷ ban Đặc nhiệm, gồm tập hợp những tinh hoa trí tuệ của mọi ngành sinh hoạt. Đó phải là một công trình của toàn thể những người Việt tự do ở hải ngoại, không phân biệt màu sắc cá nhân phe nhóm. Bước khởi đầu đơn giản chỉ một đô la cho mỗi đầu người mỗi năm, thì chúng ta đã có hơn một triệu mỹ kim cộng thêm với hai triệu mỹ kim nữa của Hội Y Nha Dược, Hội chuyên gia và các giới doanh thương. Sẽ không phải là nhỏ với ba triệu đô la mỗi năm để làm nền móng khởi đầu cho Dự Án 2000 ấy. Ngũ niên đầu là giai đoạn sở hữu một khu đất đủ lớn cho nhu cầu quy hoạch Công viên Văn hoá với một convention center là công trình xây cất đầu tiên: đó như một cái nôi cho sinh hoạt cộng đồng văn hoá và nghệ thuật. Chính cứ vẫn phải nghe một điệp khúc đến nhàm chán rằng người Việt Nam không đủ khả năng tạo dựng những công trình lớn có tầm vóc. Viện cớ rằng do những cuộc chiến tranh tàn phá lại cộng thêm với khí hậu ẩm mục của một Á châu nhiệt đới gió mùa, đã không cho phép tồn tại một công trình nhân tạo lớn lao nào. Nhưng bây giờ là trên đất nước Mỹ và Chính muốn chứng minh điều đó không đúng. Yếu tố chính vẫn là con người. Làm sao có được một giấc mơ đáng gọi là giấc mơ. Để rồi cái cần thiết là chất xi măng hàn gắn và nối kết những đổ vỡ trong lòng... Chính đã hơn một lần chứng tỏ khả năng lãnh đạo một tập thể trí tuệ nhất quán không làm gì trong suốt hai thập niên qua; bây giờ thì anh đang đứng trước một thử thách ngược lại, vận dụng sức mạnh cũng của tập thể ấy để phải làm một cái gì nếu không phải ở trong nước thì cũng ở hải ngoại, trong một kế hoạch ngũ niên cuối cùng của thế kỷ trước khi bước sang thế kỷ 21. Một ngũ niên có ý nghĩa của kế hoạch và hành động thay vì buông xuôi.

Chỉ qua một vài bước thăm dò Chính cảm nhận được ngay rằng quả là dễ dàng để mà đồng ý với nhau khỏi phải làm gì nhưng vấn đề bỗng trở nên phức tạp hơn nhiều khi bước vào một dư án cụ thể đòi hỏi sự tham gia và đóng góp của mỗi người kéo theo bao nhiêu câu hỏi “tại sao và bởi vì” từ ngay chính những người bạn tưởng là đã rất thân thiết của anh đã cùng đi với nhau suốt một chặng đường. Hội nghị Palo Alto sẽ là một trắc nghiệm thách đố không phải của riêng anh mà là của toàn thể Y giới Việt Nam hải ngoại.

Thay vì đứng ngoài bàng quan hội Y sĩ Thế giới sẽ tiên phong trực tiếp tham gia ngay từ bước đầu hình thành Công viên Văn hoá ấy. Đó là một chuẩn bị thao dượt, như một ấn bản gốc cho mô hình của viện bảo tàng chiến tranh Việt Nam của ISAW. Người Mỹ có dự án ISAW (Institute for the Study of American Wars) thiết lập một Quảng trường Hào hùng tại Maryland gồm một chuỗi viện bảo tàng liên quan tới bảy cuộc chiến tranh, mà người Mỹ đã trực tiếp can dự kể từ ngày lập quốc. Dĩ nhiên trong đó có chiến tranh Việt Nam, cũng là cuộc chiến tranh duy nhất có chính nghĩa mà miền Nam Việt Nam và Mỹ đã bị thua. Cung cấp dữ kiện đi tìm đáp số cho những câu hỏi vấn nạn tại sao sẽ phải là nội dung của viện bảo tàng tương lai này. Hai triệu người thoát ra khỏi nước bằng một cuộc di dân vĩ đại, họ không thể chấp nhận cuộc thất trận lần thứ hai khác lâu dài và vĩnh viễn tại Valor Park với lặp lại những gian dối lịch sử cũng vẫn do người cộng sản chủ động sắp xếp. Không phải chỉ là vấn đề ai thắng ai; nhưng đó là nhân cách chính trị của hai triệu người di dân tỵ nạn đang phấn đấu cho một thể chế chính trị tự do nơi quê nhà. Và Chính quan niệm những bước hình thành khâu viện bảo tàng Việt Nam tại ISAW phải được khởi đầu từ dự án khu Công viên Văn hoá Việt Nam năm 2000 ngay giữa thủ đô tỵ nạn. Đó là một phác thảo và chọn lọc tất cả các hình ảnh tài liệu và chứng tích của các giai đoạn Việt Nam Tranh đấu sử. Đó là nơi giúp thế hệ trẻ hướng Việt tìm lại khoảng thời gian đã mất, giúp chúng hiểu được tại sao chúng lại hiện diện trên lục địa mới này.

Giữa hai bố con Chính đang âm thầm diễn ra tranh chấp về trận địa của những giấc mơ. Giấc mơ của Toản thì xa hàng vạn dặm mãi tận bên quê nhà. Giấc mơ nào là không thể được, bên trong hay bên ngoài? Hiện thực của giấc mơ nào đi nữa không phải chỉ do hùng tâm của một người mà là ý chí của cả một tập thể cùng nhìn về một hướng, cùng trông đợi và ước ao niềm vui của sự thành tựu. Riêng Chính thì đang ao ước không phải để có một ngôi đền thờ phụng, mà là một mái ấm của Trăm Họ Trăm Con, nơi ấy sưu tập và lưu trữ những giá trị của quá khứ, nơi hội tụ diễn ra sức sống sinh động của hiện tại, và là một điểm tựa thách đố hướng về tương lai, chốn hành hương cho mỗi người Việt Nam đang sống bất cứ ở đâu trong lòng của thế giới.

Ngô Thế Vinh

Little Saigon 01/1995 – 04/2025